William

Claude

Dukenfield was born Jan.

29, 1880 in Darby, Pennsylvania, just across the

Philadelphia city line. The eldest of the five children

of James Dukenfield, an English immigrant, and Kate

Felton, a native Philadelphian, Fields lived -- to hear

him tell it in later years -- a Huck Finn sort of

childhood in which he left home at age 11 (after

smashing a crate over his father's head) and survived by

his wits, sleeping in a ditch or on a pool table,

stealing food and staying one step ahead of the

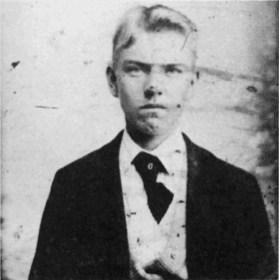

constable. But in fact, "Whitey" Dukenfield, as the

blond youth was nicknamed, often squabbled with his

father, but he lived with the family until age 18. William

Claude

Dukenfield was born Jan.

29, 1880 in Darby, Pennsylvania, just across the

Philadelphia city line. The eldest of the five children

of James Dukenfield, an English immigrant, and Kate

Felton, a native Philadelphian, Fields lived -- to hear

him tell it in later years -- a Huck Finn sort of

childhood in which he left home at age 11 (after

smashing a crate over his father's head) and survived by

his wits, sleeping in a ditch or on a pool table,

stealing food and staying one step ahead of the

constable. But in fact, "Whitey" Dukenfield, as the

blond youth was nicknamed, often squabbled with his

father, but he lived with the family until age 18.

Having left school somewhere around sixth grade, he'd worked with his father hawking fruits and vegetables, in addition to other jobs in a cigar store, a pool hall, a newsstand and a department store. More typically, Whitey could be found at one of Philly's several variety theaters, for he had taken a keen interest in juggling. Touring the circuits then were such notables as Charles T. Aldritch and O.K. Sato, Comedy Juggler, but one in particular seems to have inspired the boy most: Paul Cinquevalle, the Prince of Jugglers, a mustachioed American showman who juggled plates, cannon balls, umbrellas, even tables and chairs.

A stint with a traveling burlesque show followed, which ended when the show's manager abandoned the troupe in Kent, Ohio. But Fields had fallen for a chorus girl, Hattie Hughes; he married her and made her his assistant. For the next couple years Fields played burlesque circuits in the East and Midwest, advancing steadily toward the top of the bill. In 1901 he made his first tour of Europe, and his silent Tramp Juggler act was a hit wherever he played. In 1903 Fields added his trademark routine, the trick pool table, and it wasn't long before critics heralded him as the greatest comedy juggler of his generation. Fields began his self-education around this time, filling a steamer trunk with volumes of the classics -- Dickens, Twain, Hardy, Milton, Shakespeare, Dumas -- and reading them voraciously between performances.

It was during these years that Fields, equipped with a little clip-on mustache, made his ventures into silent film, commencing with Pool Sharks (1915). Except for Sally of the Sawdust (D. W. Griffith's 1925 filmed version of Poppy), these early films fared poorly with critics and at the box office. It was also during these years that Fields gave up on his marriage and began a series of relationships with chorus girls. One of these led to an illegitimate son, William Rexford Fields Morris, born in 1917 to Bessie Poole, a Follies dancer. Poole gave the boy up for adoption and died 10 years later in a bar fight. (Fields had had Poole sign a document stating he was in no way responsible for the child, but in fact he supported the boy through adulthood. Morris would later track down Fields in Hollywood and show up at his door, asking to see his father. Fields reportedly instructed his butler: "Give him an evasive answer. Tell him to go fuck himself.") In 1930, Fields made his first "talkie," The Golf Specialist, for RKO (at a New Jersey studio), featuring the golf routine he'd made famous in the Vanities and in a silent film, So's Your Old Man, and for the first time film audiences heard his distinctive, raspy drawl. The next year, with the popularity of sound pictures and the death of Vaudeville, Fields moved to Hollywood and soon found a home at Paramount Pictures. He stole the show in 1932's Million Dollar Legs, an oddball comedy about a nation of Olympic-calibre athletes, but tentative studio executives kept trying to "pair him up" with other comic actors like Alison Skipworth and Charlie Ruggles. In 1932 and 1933, Fields moonlighted with director Mack Sennett to make four shorts that would showcase Fields' stage routines: The Dentist, The Fatal Glass of Beer (a re-working of "The Stolen Bonds"), The Pharmacist and The Barber Shop.

By 1936 his drinking caught up with him, and he tried to "dry out" a couple times. Paramount wouldn't renew his contract, so he accepted radio guest appearances (notably with ventriloquist Edgar Bergen and his dummy, Charlie McCarthy) that, to his surprise and delight, made him more popular than ever. In 1939, back on his feet, he negotiated a deal with Universal Studios, where he would make his most famous films: You Can't Cheat an Honest Man (with Bergen and McCarthy); My Little Chickadee, with Mae West co-writing the script; The Bank Dick, and Never Give a Sucker an Even Break (both described below).

After a protracted court battle,

Fields' wife Hattie was awarded his estate, valued at

more than $700,000. His mistress of many years,

Carlotta Monti, and his illegitimate son went home

empty handed. Although rumored to have dictated an

epitaph -- "On the Whole, I'd Rather Be in

Philadelphia" -- Fields' columbarium niche at Forest

Lawn in Glendale, California simply reads "W.C. Fields

/ 1880-1946." |

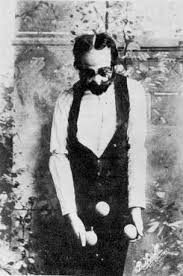

Young Dukenfield began practicing

fervently, starting with his father's produce, and

worked up routines with balls, hats, cigar boxes and a

cane. Thanks to his tenure at the pool hall, he also

perfected a host of billiards tricks. But, determined

to make his act stand out, Dukenfield added touches of

comedy to his juggling, like "accidentally" dropping

an object, only to deftly snatch it on the rebound or

send it caroming off a startled assistant and back

into the flow. In January 1898 he began performing at

local Masons halls and such venues as "Wm. C. Felton"

but soon -- attired in tattered clothes and fake beard

-- became "W.C. Fields, Tramp Juggler." By August of

that year he'd secured a job at Plymouth Park, an

amusement park in Norristown, PA. Proprietor J.

Fortescue soon moved the popular young juggler to his

Atlantic City venue, Fortescue's Pavillion.

Young Dukenfield began practicing

fervently, starting with his father's produce, and

worked up routines with balls, hats, cigar boxes and a

cane. Thanks to his tenure at the pool hall, he also

perfected a host of billiards tricks. But, determined

to make his act stand out, Dukenfield added touches of

comedy to his juggling, like "accidentally" dropping

an object, only to deftly snatch it on the rebound or

send it caroming off a startled assistant and back

into the flow. In January 1898 he began performing at

local Masons halls and such venues as "Wm. C. Felton"

but soon -- attired in tattered clothes and fake beard

-- became "W.C. Fields, Tramp Juggler." By August of

that year he'd secured a job at Plymouth Park, an

amusement park in Norristown, PA. Proprietor J.

Fortescue soon moved the popular young juggler to his

Atlantic City venue, Fortescue's Pavillion.

When Hattie became pregnant, Fields

dispatched her to Philadelphia. She would never return

to the stage, for it seemed she now preferred a more

"respectable" lifestyle, and for the next 30 years

Fields would send her a weekly check, although never

an amount to her satisfaction. Hattie converted to

Catholicism and did the same for their son, Claude,

which further angered Fields, who felt religion was

"for chumps," and the couple's relationship became a

battlefield. Fields' later films would reflect this

domestic anguish. But Fields, now in the highest rank

of entertainment, continued to tour the world until

1915, when he settled in New York and began a long

tenure with Flo Zigfield's Follies, co-starring with

such luminaries as Al Jolson, Ed Wynn, Leon Errol,

Bert Williams, Fanny Brice and Will Rogers. In this

venue he juggled some but concentrated on developing

comedy routines, most of which would later show up on

film, such as A Game of Golf, The Back Porch, The

Picnic, and The Stolen Bonds. He also appeared in

competing revues such as George White's Scandals and

Earl Carroll's Vanities. In 1923 Fields starred in a

Broadway hit, Poppy, as Professor

Eustace McGargle, F.A.S.N., a character into which

Fields was able to funnel his experiences with con

men, medicine show characters, fairground barkers and

the like. Blended with a dollop of his Dickensian

favorite Mr. Micawber, this synthesis formed one of

the two charcters (besides the henpecked pater

familias) that Fields would play from here on.

When Hattie became pregnant, Fields

dispatched her to Philadelphia. She would never return

to the stage, for it seemed she now preferred a more

"respectable" lifestyle, and for the next 30 years

Fields would send her a weekly check, although never

an amount to her satisfaction. Hattie converted to

Catholicism and did the same for their son, Claude,

which further angered Fields, who felt religion was

"for chumps," and the couple's relationship became a

battlefield. Fields' later films would reflect this

domestic anguish. But Fields, now in the highest rank

of entertainment, continued to tour the world until

1915, when he settled in New York and began a long

tenure with Flo Zigfield's Follies, co-starring with

such luminaries as Al Jolson, Ed Wynn, Leon Errol,

Bert Williams, Fanny Brice and Will Rogers. In this

venue he juggled some but concentrated on developing

comedy routines, most of which would later show up on

film, such as A Game of Golf, The Back Porch, The

Picnic, and The Stolen Bonds. He also appeared in

competing revues such as George White's Scandals and

Earl Carroll's Vanities. In 1923 Fields starred in a

Broadway hit, Poppy, as Professor

Eustace McGargle, F.A.S.N., a character into which

Fields was able to funnel his experiences with con

men, medicine show characters, fairground barkers and

the like. Blended with a dollop of his Dickensian

favorite Mr. Micawber, this synthesis formed one of

the two charcters (besides the henpecked pater

familias) that Fields would play from here on.

But back at Paramount, Fields

gradually brought studio execs around, confounding

them when he launched into ad-lib but mollyfying them

with good reviews. In 1933, he stole the show in International

House as Prof. Quayle, a "wrong-way

Corrigan" who lands his autogyro on a hotel roof in

China. Before long he'd wrested creative control of

his films from the studio and began to rework some of

his silent films. Though flops the first time around,

these remakes began to catch on: You're Telling

Me, a remake of So's Your Old Man(1926);

It's A Gift , from The Old Army

Game (1926); Man on the Flying

Trapeze, from Running Wild (1927),

and Poppy. And in 1935 he prevailed

upon Paramount to lend him to MGM to play his favorite

Dickens character, Micawber, in David

Copperfield, a performance critics

universally praised.

But back at Paramount, Fields

gradually brought studio execs around, confounding

them when he launched into ad-lib but mollyfying them

with good reviews. In 1933, he stole the show in International

House as Prof. Quayle, a "wrong-way

Corrigan" who lands his autogyro on a hotel roof in

China. Before long he'd wrested creative control of

his films from the studio and began to rework some of

his silent films. Though flops the first time around,

these remakes began to catch on: You're Telling

Me, a remake of So's Your Old Man(1926);

It's A Gift , from The Old Army

Game (1926); Man on the Flying

Trapeze, from Running Wild (1927),

and Poppy. And in 1935 he prevailed

upon Paramount to lend him to MGM to play his favorite

Dickens character, Micawber, in David

Copperfield, a performance critics

universally praised.  But Fields ignored his doctors' pleas

for moderation, and his health once again

deteriorated, and except for a few more cameo roles at

other studios, W.C. Fields' career had come to an end.

In 1945, crippled by arthritis and weakened by

cirrhosis of the liver, he moved out of his Bel Air

home into nearby Las Encinas Sanitarium, where in

December 1946 he lapsed into a coma. He came out of it

on Christmas Day long enough to wink to the friends

gathered around his bed, then surrendered to "the man

in the bright nightgown," as Fields had often

characterized the Grim Reaper.

But Fields ignored his doctors' pleas

for moderation, and his health once again

deteriorated, and except for a few more cameo roles at

other studios, W.C. Fields' career had come to an end.

In 1945, crippled by arthritis and weakened by

cirrhosis of the liver, he moved out of his Bel Air

home into nearby Las Encinas Sanitarium, where in

December 1946 he lapsed into a coma. He came out of it

on Christmas Day long enough to wink to the friends

gathered around his bed, then surrendered to "the man

in the bright nightgown," as Fields had often

characterized the Grim Reaper.

Man on the

Flying Trapeze (1935): not a circus

picture, actually the tale of Ambrose Wolfinger, a

henpecked "memory expert" who reports his

mother-in-law dead to get the afternoon off to go to a

wrestling match. This neglected masterpiece features

Fields' mistress, Carlotta Monti, as his secretary; The Old Fashioned Way (1934):

The Great McGonigle and his "happy little family of

the theatre" put on The Drunkard in a backwater town.

One priceless act of this "show within a show" is a

recreation of Fields' juggling act, complete with the

legendary cigar-box trick; The

Bank Dick (1940): layabout Egbert Sousť

lucks into a job as security officer at a bank where

his daughter's fiance works. He persuades the lad to

embezzle $500 to invest in a beefsteak mine. Stanley

Kubrick listed this as one of his favorite films; Never Give a Sucker an Even Break

(1941): Fields' last major work, a quirky broadside at

Hollywood. Fields plays himself in battle with a film

producer, trying to sell a script wherein he jumps out

of an airplane after his flask and lands unharmed in a

Russian village in Mexico. There he woos the rich Mrs.

Hemoglobin (Margaret Dumont), who lives atop a

mountain with her virginal daughter (Susan Miller, who

belts out a show-stopping version of "Comin' Thro' the

Rye"). One of Federico Fellini's favorite films.

Man on the

Flying Trapeze (1935): not a circus

picture, actually the tale of Ambrose Wolfinger, a

henpecked "memory expert" who reports his

mother-in-law dead to get the afternoon off to go to a

wrestling match. This neglected masterpiece features

Fields' mistress, Carlotta Monti, as his secretary; The Old Fashioned Way (1934):

The Great McGonigle and his "happy little family of

the theatre" put on The Drunkard in a backwater town.

One priceless act of this "show within a show" is a

recreation of Fields' juggling act, complete with the

legendary cigar-box trick; The

Bank Dick (1940): layabout Egbert Sousť

lucks into a job as security officer at a bank where

his daughter's fiance works. He persuades the lad to

embezzle $500 to invest in a beefsteak mine. Stanley

Kubrick listed this as one of his favorite films; Never Give a Sucker an Even Break

(1941): Fields' last major work, a quirky broadside at

Hollywood. Fields plays himself in battle with a film

producer, trying to sell a script wherein he jumps out

of an airplane after his flask and lands unharmed in a

Russian village in Mexico. There he woos the rich Mrs.

Hemoglobin (Margaret Dumont), who lives atop a

mountain with her virginal daughter (Susan Miller, who

belts out a show-stopping version of "Comin' Thro' the

Rye"). One of Federico Fellini's favorite films.