|

‘Rock and Roll Star' to Come Out" It was spring 1972. Freddie, a bass player with an underground band, was browsing in Manny's Music Store in Manhattan when a man named Claude came in asking to see some Fender Twin tweed amplifiers. Manny's had none, but Freddie had overheard the query and recommended a man on Long Island who he knew was well stocked, at whose house he was crashing at the moment: Ron DeMarino, guitarist with the globe-trotting Lester Lanin's Society Band and proprietor of a guitar repair/restoration shop. That day DeMarino got a call from Claude. Did DeMarino have a Fender Twin tweed for sale, and could he bring it into New York City? Yes and no, DeMarino answered; he had

several tweeds but he was a busy man. But Claude persisted. If a meeting could be arranged, would DeMarino bring the amp? DeMarino was intrigued, and a meeting was set for 10:30 p.m. at Butterfly Studios, a small facility on the Lower West Side. "So I went there, no amps, just to see what the thing was all about, and I hung around . . . there was a lot going on. They were building a mobile recording unit, putting a sixteen-track recorder into a bread truck . . . Elephant's Memory was rehearsing and I got to meet the guys, and some Hell's Angels that were hanging out. At around 11 o'clock, I was about to take off when a limo pulled up. The doors open, and out comes the driver, who was an ex-FBI guy, Yoko Ono and, sure enough, John Lennon." "I said hello to him. I don't get flustered, because quite frankly, in what I do I am just as big a star as the biggest stars. I am a great guitar repairman, a great refinisher and a great restorer, so quite frankly I walk proudly, and I did not get ga-ga. He liked that. From that meeting, I told him I'll bring any twins that you want, and sold him a lot of stuff after that — tons of stuff. And from that, he trusted me and and I became his final word on anything he bought." Besides buying equipment from DeMarino, Lennon began entrusting his guitars to him. "Just about every guitar he had came through here," he says. "John liked his guitars, but he didn't coddle them . . . generally there was a real looseness on all his instruments. He had tons of guitars. Equipment was walking in and out all the time. Nobody was stealing any of them, but it would not be uncommon if there were 40 guitars, and he not know where 20 of them were." One of the first guitars Lennon brought to DeMarino was a ‘54 Les Paul that needed tweaking and refinishing. "That thing was absolutely gorgeous when it left here. Three weeks after I gave it to him the thing was a wreck! He spilled something on it, it ate through the lacquer, and so on." It wasn't long before Lennon presented DeMarino a rather singular guitar to look after. "He brought the case to Butterfly Studios, and I opened it up, and I couldn't believe it." It was the 1958 Rickenbacker 325 Lennon had bought in Hamburg. "It had, like, two flat-wound strings, one string missing, the wrong string on the wrong place, it had some wire-wound string, it was like a disaster. I mean, you're looking at it [thinking] ‘This can't be!'" Then he looked inside. "The electronics were terrible — the amount of cold-solder joints, and so on. We had an honest relationship, and I had no hesitation to tell him — it was done terribly. Now I never asked if he had done all that messing with it, so whether he did it or had someone else do it, I can't say for absolute certain. . . but he did like to fiddle-faddle with everything, and he'd just fiddled it to the point where he couldn't play it." "I had to rewire the whole thing.

I had to call Rickenbacker . . . and told them I need

the wiring diagram, and they sent me the wrong

diagram. They have no clue what's going on over

there." DeMarino eventually got the wiring

straightened out, and then tackled the finish.

"John wanted the paint taken off, and just to show my

ignorance, I didn't know at the time that it was

naturally a honey brown color, and I tried to talk him

out of it. I said ‘John, you can't do

that. This guitar is widely noted as being

black,' and he says [Liverpool accent] ‘You've

got to do it. It's the way I want it!' I

said, ‘OK, if you want it like that, its yours.

But you know, the pickguard is all scratched up — can

I put on a new pickguard?' He says ‘Yes.'

I say, ‘Can I have the old one?' He says, ‘You

can have it.' Then I took the tuning machines

off, which were Grover open-backs, and the strings,

which somebody glommed; somebody got a souvenir."

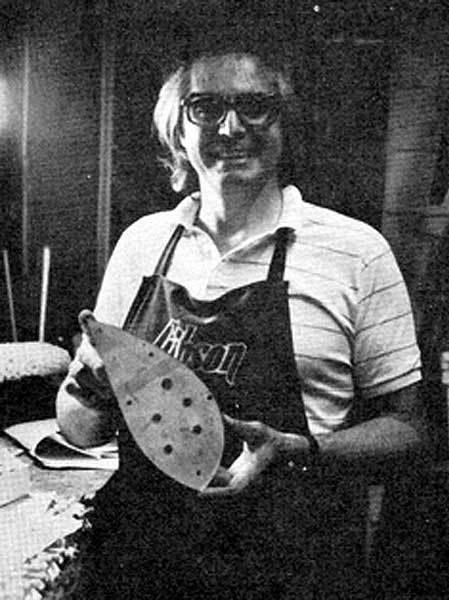

DeMarino told this writer that he replaced the pickguard with another gold one, but modern photos of the 325 show it with a white one, so go figure. DeMarino auctioned off the original pickguard, along with the Grovers, in 2014. Today he sells authentic replicas of the pickguard to those tricking out their 325V59s. "When they [Rickenbacker] did the reissues," he maintains. "they never got it right.") Regarding the paint job on the guitar: "I automatically assumed that he [Lennon] did it. Burns [of London] might have done a black finish on that 325 originally, but I think John went over it because there were brush marks in that thing, man, and I'm talking about brush marks. That job was done with a paint brush, maybe a tooth brush." But DeMarino went to work and revealed the natural maple beneath the paint, and the results delighted Lennon. DeMarino continued to work on Lennon's instruments until the mid-'70s, when DeMarino's touring schedule, and Lennon's retirement, slowed their interaction. But DeMarino has many fond memories of being in Lennon's inner circle during the New York years. "He trusted me, and we got along very well . . . if he was going out to dinner, I was included; if he was going somewhere and they were trying to lose half their entourage, I wasn't part of the entourage that was getting lost, so with there was a lot of respect." He recalls hanging out at the Record Plant, helping simulate through overdubs a live audience for one track (with David Peel, one of the Ramones and a few others). "John wasn't getting drunk, but we certainly were. John was cool. He always maintained his integrity. I never saw him get high, I never saw him get drunk." DeMarino remembers sitting alone in the Record Plant with his wife and Lennon after a session as "the rock and roll star" stretched out on the carpet, a handbag for a pillow, "talking for hours about children, life, everything. He was a genuine, wonderful guy." Perhaps most fondly, DeMarino remembers being in bed with the Lennons. "John stayed in bed a lot, and so did she. There would be like, 20 or 30 people in and out of the bedroom in the course of a couple hours, asking him questions . . . In order to get any thing done I had to sit on the bed with a clipboard and write down notes of what he wanted me to do on his next guitar, so you can say I was in bed with John and Yoko." Before Lennon's death, he'd asked DeMarino to schedule some time to work on his Epiphone Casino, which DeMarino had tweaked a few years earlier. Lennon "generally seemed to be going back to the original finishes," DeMarino says, "and I think he planned to refinish it in the original sunburst. One of John's cohorts told me John took the finish off himself because he wanted to open up the tone, but I wonder about that; his character wasn't like that. He was not so astute to say, ‘oh the lacquer changes the characteristics,' or whatever. Like I said, he liked to fiddle around with them, just go in and do things." Today DeMarino continues to play and run his equipment repair and restoration shop on Long Island, but a visitor will see no pictures of him and Lennon displayed. "I didn't gawk at him or fondle him or take pictures," he says. "That's the way it was, and that's why I was there."

Thanks to Ron DeMarino and Jo Ann Laverde (c) 2000 - 2017 John F. Crowley Back to Lennon's Guitars |